|

As late as Monday, February 12, the rebel generals still were not sure which city Sherman planned to attack. But by Wednesday, February 14, Sherman took Branchville, and the South Carolina Rail Road, the second of three, was in Union hands. From here, Sherman controlled the South Carolina rail line into both cities. Only the Northeastern was left open for Confederate retreat, so Beauregard ordered Hardee to complete an evacuation immediately before they lost the last railroad that connected Charleston with Florence to the north. Engineers including Henry Suder were ordered to push their engine hard along the Northeastern line to take the soldiers and supplies north.

On Friday night, February 17, and Saturday morning, February 18, General Hardee’s staff completed the evacuation of Charleston’s defenders on Beauregard’s orders. The garrisons on Sullivan’s Island and Point Pleasant were quietly withdrawn, as were the troops around Moultrie and Sumter. Then the garrison on James Island and the remaining troops in the city were put on trains or marched along Northeastern Railroad’s track toward Florence on the only route left to them. Beauregard’s rebel army defending Columbia gave only token resistance before retreating to the east; the army in Charleston would give none at all.

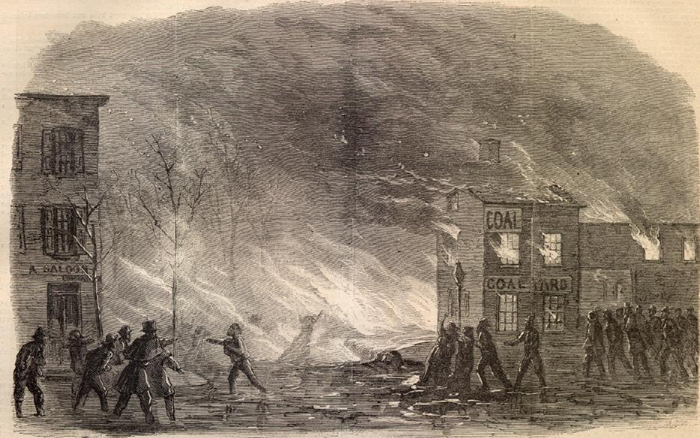

“Early Saturday morning, before the retirement of General Hardee’s troops, every building, warehouse or shed stored with cotton, was fired by a guard detailed for that purpose,” reported the Charleston Courier on February 20. “The [fire] engines were brought out, but with the small force at the disposal of the Fire Department, very little else could be done than to keep the surrounding buildings from igniting.”

In Charleston these final orders would be carried out that night and the following morning to leave nothing for the Union army. Cannons were spiked, quartermaster’s stores were destroyed, and ironclad’s and ships were scuttled. Cotton storehouses filled with an estimated 6,000 bales waiting to be shipped were set on fire. Much of the extra ammunition was exploded. The bridge connecting Charleston with James Island was burned, creating a firestorm to the west. Around seven o’clock on Saturday morning a huge explosion was heard as a cache of ammunition was destroyed near one of the larger commissary stores. With that, as though on queue, separate fires erupted across northern Charleston.

“As our provisions were exhausted and we were informed that the commissary stores were being given for Confederate money, I collected what amount we had in the house and with my servant started for the quartermaster’s department at the head of Columbus street,” recalled Pauline Dufort. “Before reaching there a tremendous explosion which shook the city to its very foundation brought us to a halt. Crowds of frightened women and children, white and black, came running toward us, some of them saying, “Don’t go there,” “you’ll be blown to pieces.”

Dufort and others stood on Meeting Street at the railroad workshops for the South Carolina rail line, not knowing what to do. A passerby alerted the confused women that “those workshops are about to be blown up.” Dufort ran home and sent a message to a friend, asking if she could move her family to their house farther north on Line Street, and the response was that workshops there “were also to be blown up” and her friend was fleeing. Later she received word that the order to destroy the South Carolina Railroad workshops was countermanded.

The last Confederate troops moved the remaining supplies and ammunition to the Wilmington Depot on the Northeastern rail line at Chapel and Alexander Streets, and loaded as much as possible on the last train heading north. After that train left the station, the unguarded depot was still filled with commissary supplies, damaged ammunition, and 200 kegs of gunpowder. It was probably the only large cache not yet demolished by the retreating Confederates.

Aware of burning cotton bales at one end of the depot, but unaware of the roomful of gunpowder stored next to the burning cotton, and the trail of gunpowder between the two, starving civilians entered the station and gathered what they could. Henry Suder’s wife, Lizzy, was also there. She had two small boys at home, but she came to the station that cold, panicked morning to see Henry before he left the station, shuttling soldiers to the north.

“But our trials were not yet ended, for there came another terrible explosion - louder than any yet - the smoke of which darkened the sun as its hideous folds curled skyward,” wrote Dufort. “It was the Northeastern Railroad depot that had been blown up, and with it a number of persons who had gathered there in search of provisions. Some were killed outright and their mangled bodies and limbs were scattered and buried under the burning ruins.”

German-born Adolf F. C. Cramer, the son of a teacher, was eighteen at the time and kept a small diary now owned by the South Carolina Historical Society. “Awful catastrophy [sic] and loss of life at the N.E. RRoad about 9 o’clock Saturday morning was [burned] which contained provision [sic] of the [Army.] Citizenry went in large and small to get provisions. When over 200 men, women and children had got in[,] the RRoad depot blew up & killed more or less all.”

“I was in Charleston on the night before and the morning it was evacuated, and was put in charge of a detail of about 75 men to load what cars we could ahead of us,” wrote Lt. Moses Lipscomb Wood in his “War Record.” Wood was in charge of Company F of the 15th South Carolina Volunteer Infantry regiment. “We had not been out of the depot long before the women and children rushed in to get whatever they could. The depot was filled with powder and explosives and caught on fire and was blown up – causing the most pitiful sight I saw during the war. Women and children, about 250, were killed and wounded, and some were carried out by where we were in line on the streets, badly mutilated with their clothing burned off.”

The fire resulting from the huge explosion spread immediately to surrounding buildings, and first destroyed the residence of Dr. Seaman Deas on the northwest corner of Chapel and Alexander Streets. Before 9:00 Saturday morning, the fire spread to the buildings on the other side of Chapel, and became unmanageable. “All the buildings embraced in the area of four squares on Chapel, Alexander, Washington, and Charlotte Streets, to Calhoun Street, with few exceptions, were destroyed,” reported the Charleston Courier.

Jump to Page 1 | 2 | 3

|